Environmental democracy is rooted in the idea that meaningful public participation is critical to ensure that land and natural resource decisions adequately and equitably address citizens’ interests. At its core, environmental democracy involves three mutually reinforcing rights:

- the right to freely access information on environmental quality and problems

- the right to participate meaningfully in decision-making

- the right to seek enforcement of environmental laws or compensation for harm.

Protecting these rights, especially for the most marginalized and vulnerable, is the first step to promoting equity and fairness in sustainable development. Without essential rights, information exchange between governments and the public is stifled and decisions that harm communities and the environment cannot be challenged or remedied. Establishing a strong legal foundation is the starting point for recognizing, protecting and enforcing environmental democracy.

The international community first recognized these rights as part of Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which 178 governments signed. The legally binding Aarhus Convention, established by the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) in 1998, now has 47 ratifying parties (46 countries and the European Union). The Aarhus Convention defines minimum standards and obligates parties to the convention to implement these rights. It also creates a compliance mechanism that is accessible to citizens from the countries that are parties to the convention.

While these rights are broadly acknowledged to be central to responsive, fair, and effective environmental governance, the extent to which countries have established them through laws and regulations has yet to be systematically measured. If environmental democracy is to serve sustainable development, rights of access to information, participation, and justice on environmental matters need to be recognized and established by the laws of a country. Measuring the extent to which the laws of a country establish and recognize environmental democracy rights is essential to an understanding of whether these rights have true force. “Measuring the extent” means not merely determining whether laws exist, but the breadth of their coverage across the range of environmental decision making processes and how proactively they address barriers and constraints to the public’s fulfilling these rights. These could include requirements for timely information release, for public participation at the earliest stages of decision making (rather than late-stage consultation), and to ensure the public can challenge the effectiveness government agencies if enforcement of the law is lacking.

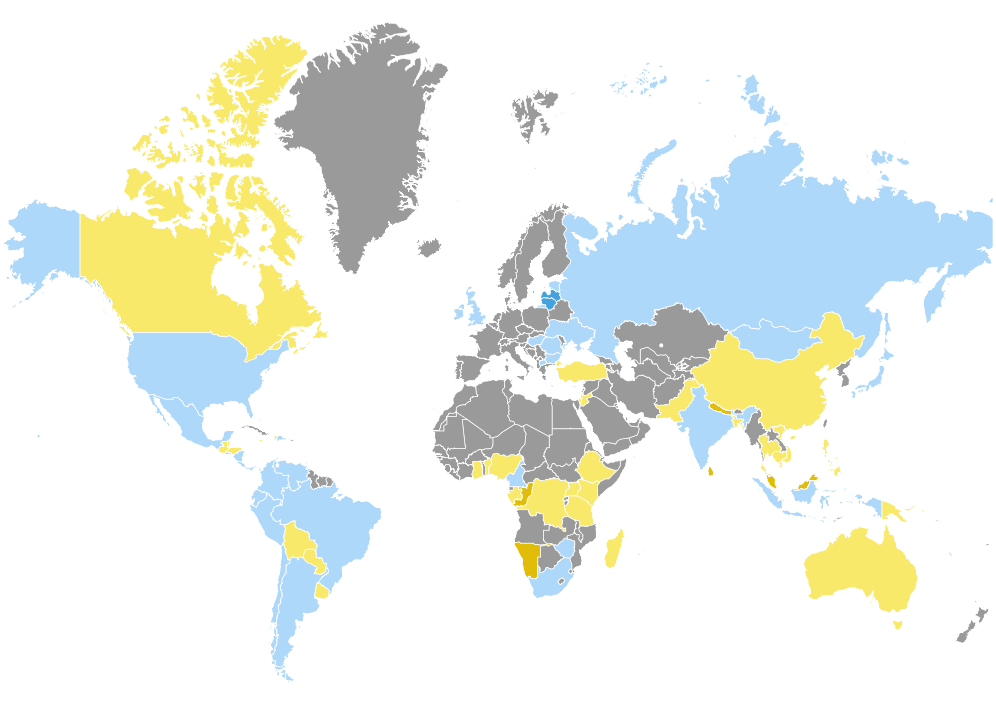

The Environmental Democracy Index was developed by The Access Initiative (TAI) and World Resources Institute (WRI) in collaboration with partners around the world. The index evaluates 70 countries, across 75 legal indicators, based on objective and internationally recognized standards established by the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Bali Guidelines. EDI also includes a supplemental set of 24 limited practice indicators that provide insight on a country’s performance in implementation. The national laws and practices were assessed and scored by more than 140 lawyers around the world. Country assessments were conducted in 2014 and will be updated every two years. Scores are provisional until September 15th, 2015 as results are being shared with governments and civil society for feedback until July 15.

EDI is a unique online platform that aims to raise awareness, engage audiences and strengthen environmental laws and public engagement. It includes:

- In-Depth Country Information. The platform provides in-depth information and scoring for 70 countries, including a summary of strengths and areas for improvement, and contextual information to help users better understand the economic and demographic situation of a country.

- Country Comparisons. EDI allows users to compare countries’ performances at multiple levels and download data on environmental democracy measures.

- Rankings. Countries around the world are ranked on their national laws according to their progress in legislating environmental democracy.

- Government Feedback. To promote a collaborative dialogue around environmental democracy, each country page provides a space for the government to respond to their country’s scores. All countries in the index will be given the opportunity to respond to their individual assessment. Feedback is expected until July 15 and scores will be final as of September 15th, 2015.

- Public and Civil Society Engagement. EDI is a powerful tool that will increase transparency around environmental laws. The country assessments involved extensive consultation and input from civil society. The platform creates a free, public space for sharing information and dialogue.