Environmental democracy is rooted in the idea that meaningful public participation is critical to ensure that land and natural resource decisions adequately and equitably address citizens’ interests. At its core, environmental democracy involves three mutually reinforcing rights:

Protecting these rights, especially for the most marginalized and vulnerable, is the first step to promoting equity and fairness in sustainable development. Without essential rights, information exchange between governments and the public is stifled and decisions that harm communities and the environment cannot be challenged or remedied. Establishing a strong legal foundation is the starting point for recognizing, protecting and enforcing environmental democracy.

The international community first recognized these rights as part of Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which 178 governments signed. The legally binding Aarhus Convention, established by the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) in 1998, now has 47 ratifying parties (46 countries and the European Union). The Aarhus Convention defines minimum standards and obligates parties to the convention to implement these rights. It also creates a compliance mechanism that is accessible to citizens from the countries that are parties to the convention.

While these rights are broadly acknowledged to be central to responsive, fair, and effective environmental governance, the extent to which countries have established them through laws and regulations has yet to be systematically measured. If environmental democracy is to serve sustainable development, rights of access to information, participation, and justice on environmental matters need to be recognized and established by the laws of a country. Measuring the extent to which the laws of a country establish and recognize environmental democracy rights is essential to an understanding of whether these rights have true force. “Measuring the extent” means not merely determining whether laws exist, but the breadth of their coverage across the range of environmental decision making processes and how proactively they address barriers and constraints to the public’s fulfilling these rights. These could include requirements for timely information release, for public participation at the earliest stages of decision making (rather than late-stage consultation), and to ensure the public can challenge the effectiveness government agencies if enforcement of the law is lacking.

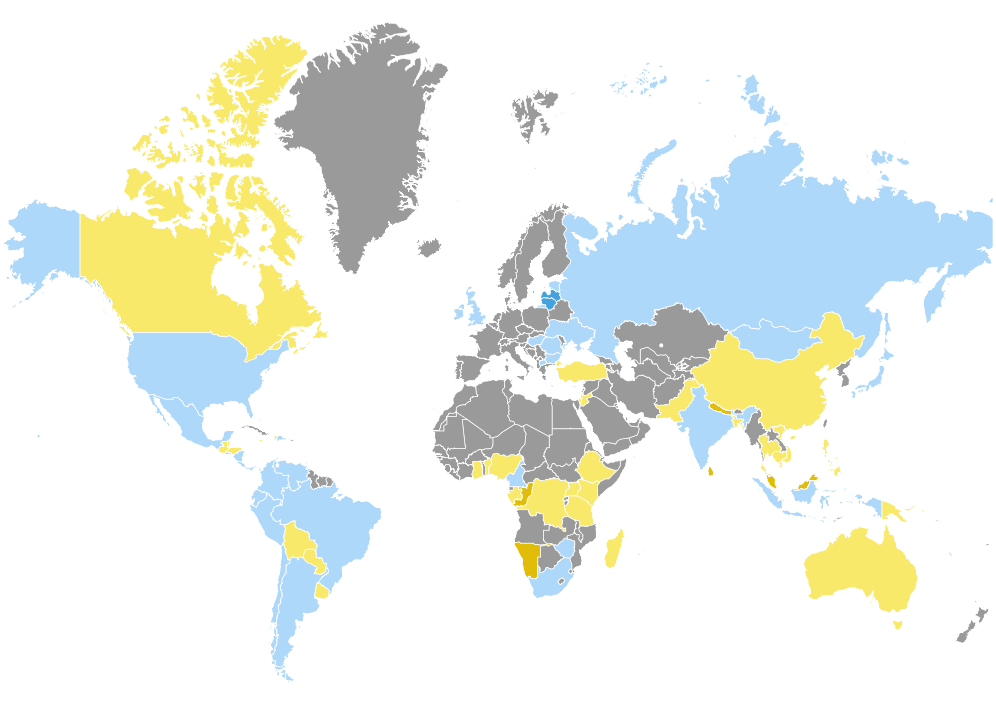

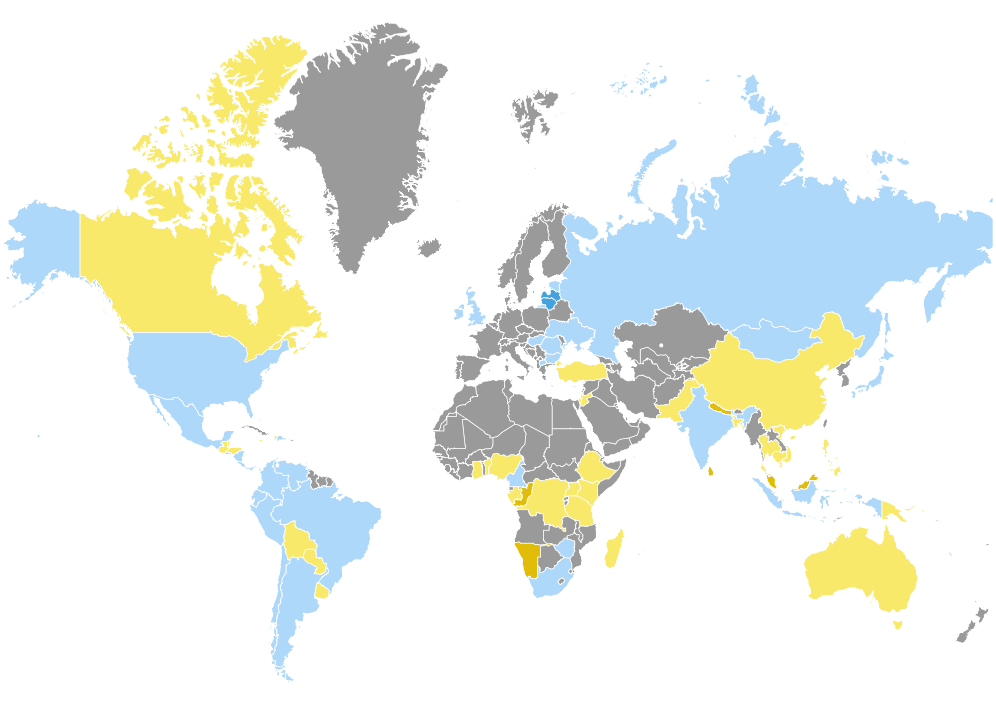

The Environmental Democracy Index was developed by The Access Initiative (TAI) and World Resources Institute (WRI) in collaboration with partners around the world. The index evaluates 70 countries, across 75 legal indicators, based on objective and internationally recognized standards established by the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Bali Guidelines. EDI also includes a supplemental set of 24 limited practice indicators that provide insight on a country’s performance in implementation. The national laws and practices were assessed and scored by more than 140 lawyers around the world. Country assessments were conducted in 2014 and will be updated every two years. Scores are provisional until August 30, 2015 as results are being shared with governments and civil society for feedback until July 15.

EDI is a unique online platform that aims to raise awareness, engage audiences and strengthen environmental laws and public engagement. It includes:

EDI measures the degree to which countries have enacted legally binding rules that provide for environmental information collection and disclosure, public participation across a range of environmental decisions, and fair, affordable, and independent avenues for seeking justice and challenging decisions that impact the environment. In addition to the legal index, EDI contains a separate and supplemental set of indicators that provide key insights on whether environmental democracy is being manifested in practice.

WRI developed the EDI indicators using the framework of the 2010 UNEP Bali Guidelines to enable governments, civil society, and other stakeholders to benchmark national legislation against internationally recognized voluntary guidelines. The UNEP Bali Guidelines consist of 26 total guidelines organized under each “pillar”—with seven guidelines each for access to information and public participation and 12 guidelines for access to justice. The guidelines unpack Principle 10 with specific guidance drawing on a body of good practice and norms developed through the experience of the Aarhus Convention and by legal advocates. Unlike the Aarhus Convention, the Bali Guidelines are voluntary. However, they represent the first time that several nations outside of the UNECE region have agreed upon specific guidelines on Principle 10 that deal with issues of cost, timeliness, standing, the quality of public participation, and several other issues on which it can be more difficult to achieve government consensus.

The EDI legal indicators assess laws, constitutions, regulations and other legally binding, enforceable, and justiciable rules at the national level. The scope of the first EDI assessment specifically includes:

EDI does not currently include marine, coastal, fisheries, or energy production and distribution laws in its assessment. While provisions that govern transparency, participation, and access to justice for decision making in these sectors may well be embedded in overarching environmental or administrative laws, and would therefore be considered, this cannot be guaranteed across the index.

All participating lawyers and environmental experts had at least five years of experience, though most were mid or late-career lawyers from civil society, academia, government, and the private sector.

WRI, in partnership with TAI partners, pilot tested the Environmental Democracy Index legal indicators in 2013 in 13 countries. The countries tested in the pilot study were Cambodia, Cameroon, Colombia, Ecuador, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Kenya, Mexico, Panama, Turkey, and Uganda. Following the pilot test, WRI revised the legal indicators and developed the 24 practice indicators. An example of a practice indicator is provided below.